NOTE: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS GRAPHIC DESCRIPTIONS OF VIOLENCE AND ABUSE THAT MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR ALL READERS.

The little boy is standing in the kitchen, balanced on one leg, both arms raised above his head.

The child in the video is shirtless and painfully thin, his entire rib cage protruding from his skin. His black hair hangs into his face as he wobbles to keep his balance. His arms shake. He is staring straight ahead.

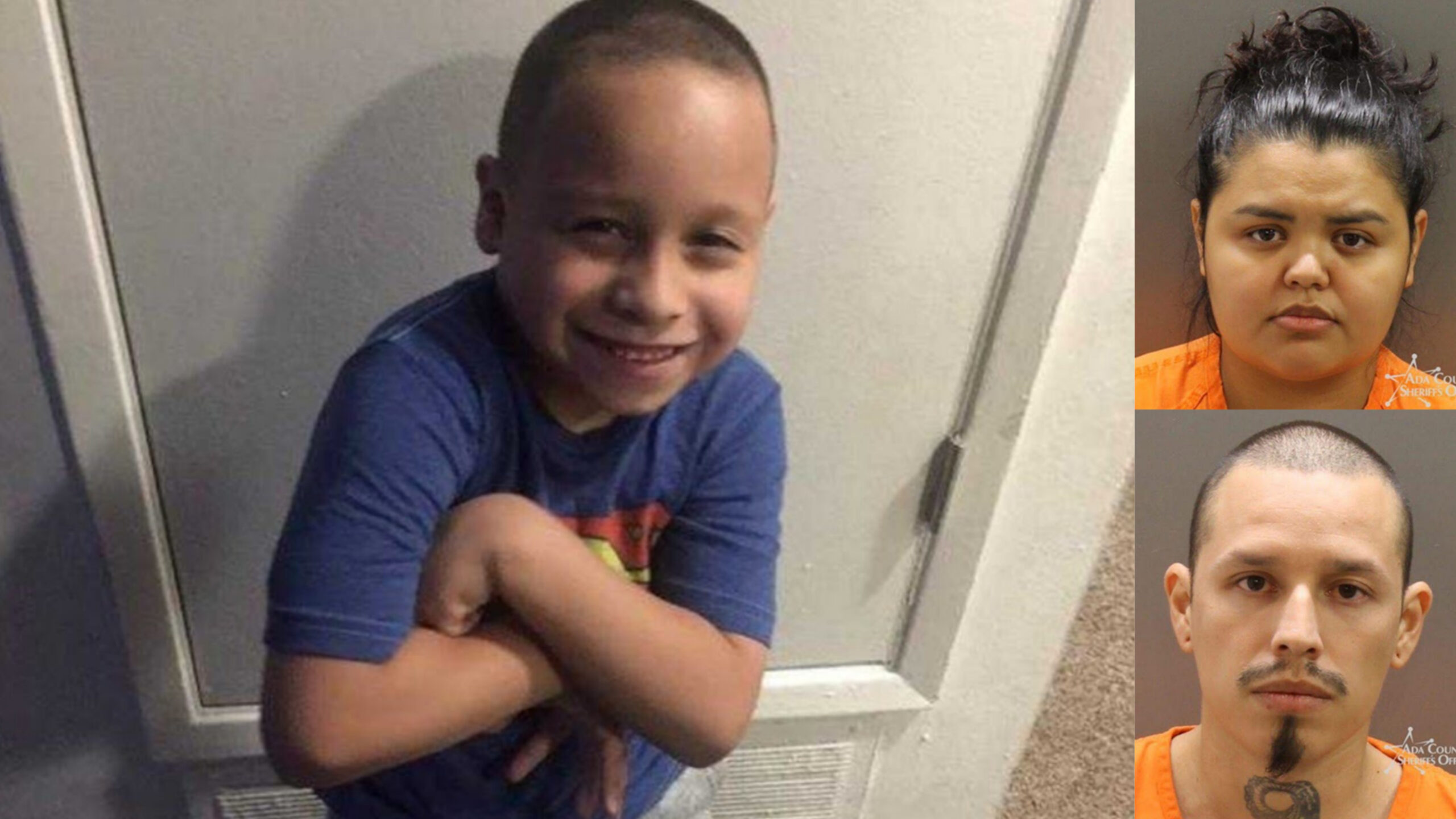

Emrik Osuna has one day left to live.

A judge on Wednesday ruled that there is enough probable cause to bind the Meridian 9-year-old’s father and stepmother, Erik and Monique Osuna, up to district court on first-degree murder charges in Emrik’s death.

The pair is accused of abusing Emrik for months leading up to his Sept. 1. death through forced exercise, starvation, and physical beatings: “torture” that continued until the boy’s body gave out and he died, prosecutors say.

Crucial to the case is video footage of the abuse that was captured on nanny cameras that were installed inside the suspects’ Meridian apartment and later recovered by police. Meridian Police Det. Eric Stoffle and Det. Matthew Ferronato said they were able to review more than two weeks of footage leading up to the evening when police found Emrik – bruised, covered in vomit, and without a heartbeat – on the living room floor.

The videos, played in court Wednesday, display the misery, hunger, and fear in which the 9-year-old spent his final days. Viewed together, they present a portrait of a child dying.

In one, recorded on August 21, Emrik can be seen sleeping in the fetal position on the floor when Monique Osuna grabs him by the hair, swinging him through the air like a ragdoll.

She drags him into the kitchen, and screams at him to begin doing jumping jacks, then slaps him violently, over and over and over. Monique later switches to smashing a spoon down onto Emrik’s head repeatedly as he shrieks, cries, and tries to shield himself from the blows.

Ferronato testified that the attack was apparently punishment for Emrik getting up in the night and drinking from cups that had been left out.

Other videos show Monique Osuna kicking Emrik across the room, yanking his hair and hitting him repeatedly with a frying pan. She can be heard calling her stepson “a f—- loser” and “a piece of sh–,” as well as telling him that she was going to make him eat his own feces and drink his own urine.

Erik Osuna is seen once in the footage hitting Emrik with a belt. He did not physically or verbally abuse the boy as often as Monique, Ferronato said, but often ignored his son and did not intervene when Monique was beating or screaming at him.

The child was also forced to do grueling physical exercises for long periods of time, including wall-sits, one-legged stands, and “inch-worms” – an exercise in which the boy was forced to walk out his hands from a standing position to a plank, then back to a standing position, raising his arms at the end and starting over.

“Each day, I would say over 12 hours a day, or thereabouts,” Ferronato said. “Sometimes it would go on, 20-plus hours of constant exercise.”

In the two weeks of footage detectives watched, Ferronato said, not once does a member of the family show affection or positive attention to Emrik. Not once does he play with a toy or a game. When his siblings, father and stepmother eat fast food for dinner, he gets none. When they head to their bedrooms for the night, he curls up on the living room floor or is forced to sleep in a hallway closet.

Erik Osuna told the police later that the morning of September 1, Monique Osuna hit the boy twice with a dog leash, then gave him some rice and water, which he threw up. After a shower, Emrik was forced again to do a one-legged stand, but was eventually permitted to lie down on the floor.

By 5 p.m. that evening, it was clear something was wrong with the 9-year-old. In a text to his wife, Erik wrote that they needed to take Emrik to the emergency room and “face it.”

“If you don’t want to that’s fine I’ll go,” he wrote. “I know you’re scared, I am too.”

According to testimony, Monique Osuna at about the same time texted her coworker and friend Hannah Berry, relaying that Emrik was unwell.

Berry testified that Monique had spoken to her previously about problems with Emrik’s behavior – complaints that ramped up in the months before the boy’s death.

Berry said she shared an opinion with her friend that the 9-year-old might have Reactive Attachment Disorder, a condition that can affect infants and children who have been neglected or abused.

Monique Osuna took Emrik to doctors, but they told her “he was a fine kid,” Berry testified. At that point, she said, Berry suggested Monique install the nanny cameras to capture the boy’s behavior, so she would have something to show medical professionals.

Berry also told her friend to make Emrik do exercise as punishment for acting out, although she said on the stand that she had not told Monique to force the child to do them for extended periods of time.

Berry eventually drove to the couple’s apartment, arriving at about 8:30 p.m. to find Emrik lying motionless on the floor in the living room.

“He was laying down and he was covered in blankets – I mean, it looked like he was sleeping,” she said.

Berry testified that she held Emrik’s hand, and discovered that it was cold to the touch.

At some point, she said, she advised Emrik’s stepmother and father to put Pedialyte into his mouth with a syringe, which they did. Later, she suggested trying to stand him up to see if he would wake up. But as they lifted the boy up, Berry said, he took his “last breath.”

“It was a deep breath, and then it was just silent,” she testified.

At that point, for the first time, someone in the apartment called 911 – a call police say came in at about 9:40 p.m. Monique began performing CPR, causing Emrik to spew a milky liquid from his nose and mouth, Berry said.

Berry said Erik made the 911 call on Monique’s phone, placed it on speaker, then handed her a bundle of nanny cams and told her to take them downstairs and put them in her car.

Erik Osuna’s attorney Edwina Elcox questioned why that statement was not picked up on the speakerphone call to dispatch, and asked why she agreed to hide those devices.

Berry responded that Erik Osuna was not speaking loudly and said that she did not realize what the bundle of cameras and cords was, testifying that she believed it was marijuana or drug paraphernalia belonging to Erik. She said that she did not immediately tell police what she had put in her car because she was “in shock” and could not recall what she had removed from the apartment.

Meridian Police Officer Scott Frazier said that when he arrived at the apartment shortly after the call to 911, he saw the 9-year-old lying on the carpet with his head towards the door. Monique was “frantic” and in tears, Frazier said, while both Berry and Erik Osuna seemed more “stoic.”

At first, Frazier said, he thought the child must have been suffering from a serious long-term illness.

“He was very emaciated, he appeared ill, his eyes were sunk into his head. He was pale,” he said.

Frazier asked Monique what the boy’s diagnosis was; she replied that he had ADHD, he testified. Frazier and another officer traded off performing CPR until paramedics arrived and took over.

The paramedics stripped off Emrik’s clothes as they treated him, Frazier said, revealing dark bruises from his inner thighs that stretched over his buttocks all the way up to his lower back. Emrik also had trauma to his penis, which the officer described as appearing as if someone had left a tightened rubber band around it.

Jana Reed, with the Ada County Paramedics, testified that Emrik was wearing a diaper, which she thought was unusual for a 9-year-old.

“When I asked why he was in a diaper, I was told ‘he kept wetting himself so I put a diaper on him,'” she testified.

Emrik had no pulse and was not breathing, Reed said. Vomit was caked in his hair and around his face.

Paramedics were able to get his heart beating again after about 20 minutes, and rushed him to St. Luke’s in Meridian. Emrik was later transferred to the pediatric ICU at St. Luke’s Children’s Hospital in downtown Boise, where he died.

A later report found the boy weighed 44 pounds at the time of his death.

Meridian Police Detective Joseph Miller, said that Monique Osuna first claimed that her stepson had been injured while “playing rough” with a group of neighborhood boys, who had hit him with a dog leash. Under questioning, however, she admitted that she had been abusing Emrik since the beginning of the year, Miller testified, with violence toward the boy escalating after the birth of her infant daughter four months prior.

Monique Osuna told Miller that she had hit the 9-year-old boy with a wetted belt, leash, backscratcher, wooden spoon, and frying pan, sometimes beating the boy with the pan “every other day” for months, he said.

“She said she thought it would teach him a lesson,” Miller said. “She said she was harder on him. She said she lashed out at him – hitting him with a pan and making him exercise while she worked, and that he only took a break when she took a break.”

Both defendants are set to enter a plea in district court April 26. First-degree murder is punishable by up to life in prison or the death penalty.

Follow Illicit Deeds on Facebook for more stories.

Enjoying our content? Your donation of any amount will help cover server costs required to keep it running, and will let us share more stories through our various support channels, and fight for justice for all victims.

Donate

Tell us your thoughts...